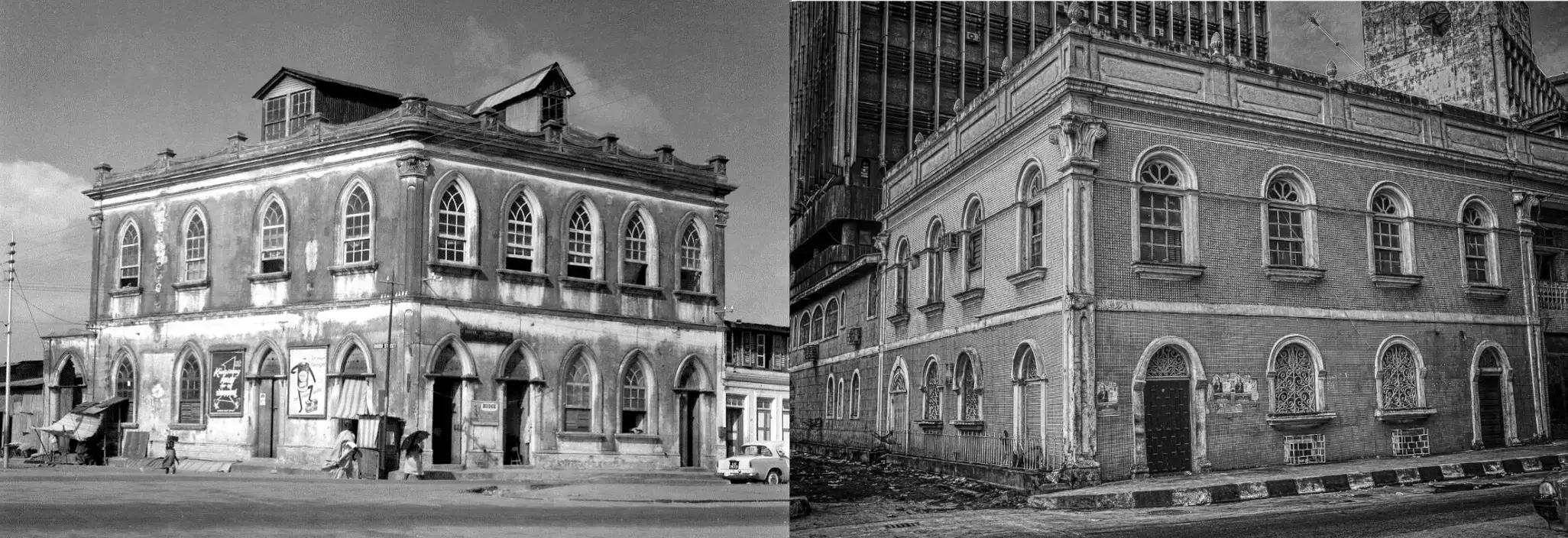

It were the skilled hands of the returnees from Brazil that built Ilojo Bar. That makes the structure as much a part of Lagos' Brazilian heritage as all the other architectural structures designed and built by the Africans who returned to the homeland, even though at no point in its history Casa do Fernandez was owned by Afro-Brazilian returnees. They were after all the go-to craftsmen and designers of this kind of structures at the time.

Between 1500 and 1870 more than 11 million Africans were kidnapped from home and shipped to the Americas in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. Out of every ten Africans leaving the Bight of Benin between 1601 and 1867, six were taken to Bahia in Brazil. After the Brazilian abolition of slave trade in 1850, and of slavery in 1888, many of those Africans decided to return to their homeland. Because of the economic possibilities, many of them ended up in cities like Lagos. These relatively well educated newcomers would change the face of Lagos.

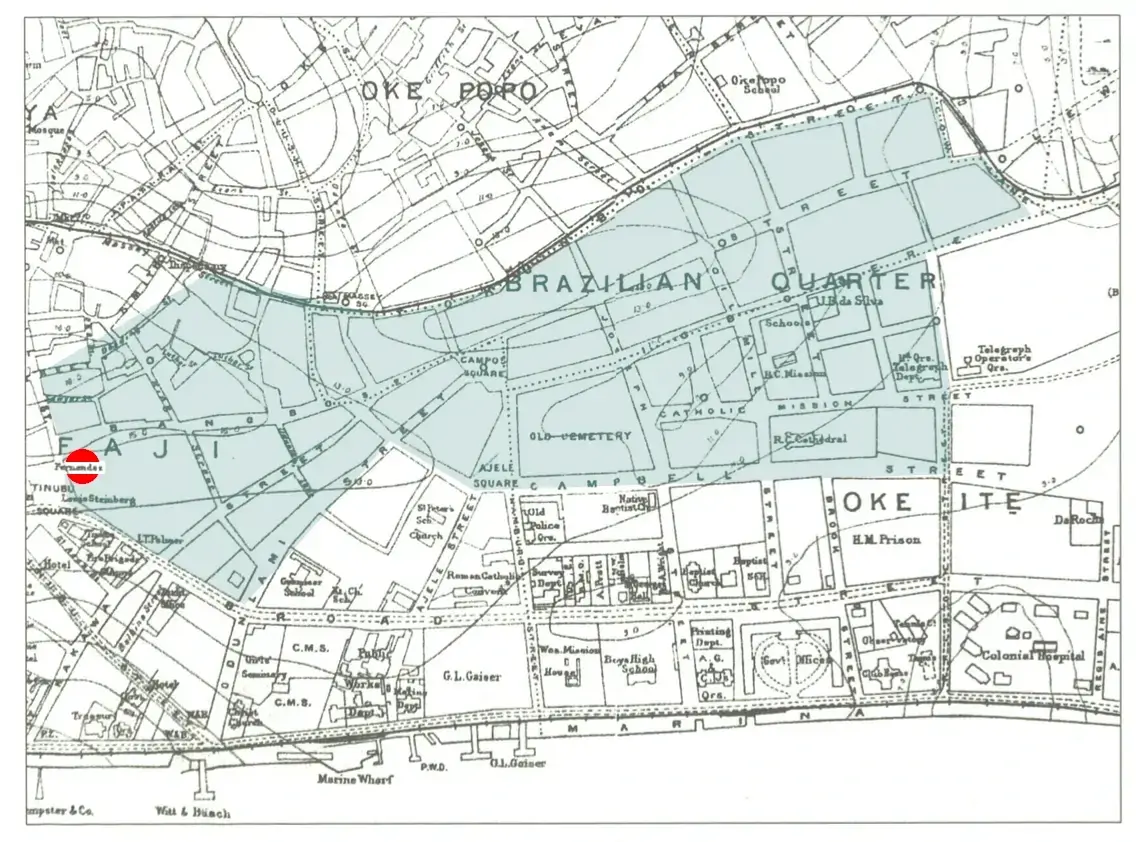

Once the Afro-Brazilians had discovered Lagos' attraction, the Aguda community in the city grew fast. In 1853, the British counted about 130 families of returnees from Brazil. In 1889 the total number of Afro-Brazilians in Lagos had jumped to five thousand, which was one in every seven residents.

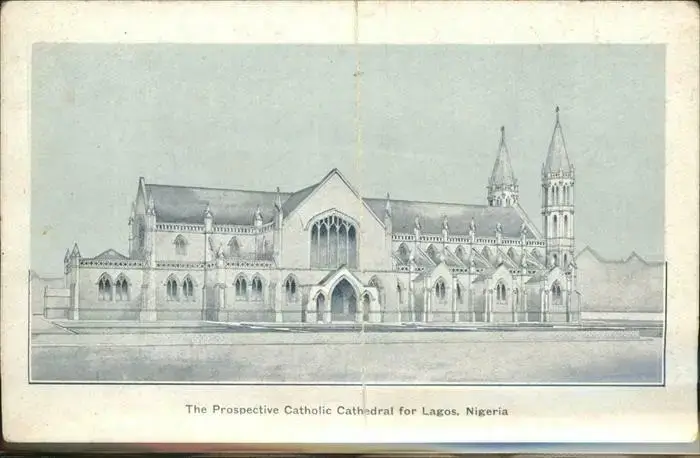

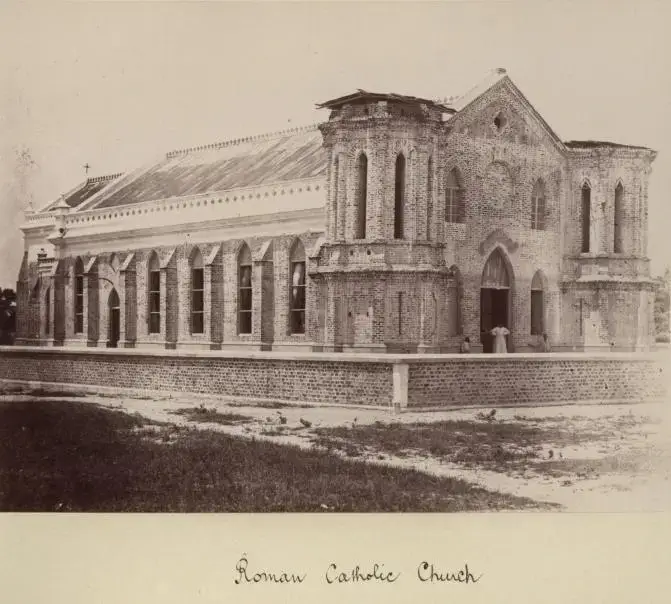

The returnees built their houses after the image of the places they had left in Brazil, with brightly painted facades and paned windows framed by cast mouldings. They changed the face of Lagos with their architecture: Holy Cross Cathedral, Shitta Bey Mosque, Water House and until 2016 Casa do Fernandez/Ilojo Bar tell the story of their craftsmanship. Casa do Fernandez was probably designed and built by one of the better known master builders such as Fransisco Nobre or João Batista da Costa.

There is a direct connection between Fernandez and master painter Walter Paul Siffre, the returnee who also worked at the Cathedral: Fernandez' Portuguese business partner and neighbour Vicente Rodrigues Guedes respected Siffre so much that he trusted him with the execution of his will. He cannot have been the only Brazilian builder of the era who had a close relationship with the Europeans on Tinubu Square.

Maybe Fernandez invited Siffre, Nobre and some others to his apartment one evening to discuss the joining of the two houses to construct his dream building. Detailed blueprints would not have been made, because they built mainly from memory. But one of the master builders would have jotted down a draft or two as they were talking.

The transatlantic trade of the returnees with Brazil in those days was intensive, with many of them sailing back and forth on a regular basis for business. According to family tradition, the great grandfather of Mr Martins of the Brazilian Descendants Association was such a person. As a young man in Oyo he got captured in one of the nineteenth century Yoruba wars, was sold to the Portuguese and shipped to Brazil. He managed to buy his freedom and returned to Lagos, where he became a supplier for the builders in the city. He supplied the roofing for the Holy Cross Cathedral, says Mr Martins, as well as building material for Casa do Fernandez. The Brazilian connection is a clear one, bot in oral and written history.